An excellent article on the BBC gives a good overview of the continuing controversy over universal lockdowns as a pandemic mitigation strategy during COVID. We now have significant data about how various countries around the world fared compared to their mitigation strategy. Interestingly, this data is unlikely to resolve the controversy.

But it can inform our decisions for the next pandemic – and there will be a next pandemic. Already the bird flu, H5N1, is extremely concerning. It is spreading in mammals, and there are occasional human cases. A single mutation may be enough to allow for human-to-human transmission. But even just as an avian pandemic, it can be economically devastating, as indicated by egg prices.

So did we learn any lessons from the COVID pandemic about the risks vs benefits of universal lockdowns and other measures? We potentially did, if we choose to listen, but there is still an extreme emotional response to the shutdowns that clouds the discourse.

From a scientific and medical perspective, we do need to look at the question from the perspective of risks vs benefits. It is a trade-off, which means there is no one correct answer. What risks are we willing to pay for the potential benefits? The best we can do is document those risks and benefits so that we can make the best informed decision.

There are various approaches to addressing the question of if there were benefits to various types of lockdown. We can model the spread of the virus, we can look longitudinally at the effects of lockdowns and lifting them in one region, or we can compare different countries with different policies. No method is perfect or yields the same results, which is why this will not end debate.

A lot of attention has been paid to Sweden, which is one of four countries that did not institute lockdowns. It is useful to compare Sweden to Norway, Finland, and Denmark because these countries are otherwise very similar. A 2024 study compared the death rate in these countries throughout the pandemic. They found that Sweden had excess deaths in 2020 compared to their neighbors, but fewer deaths in 2022. What do we make of this frustratingly ambiguous result?

From this and other data it does seem that lockdowns early on in the pandemic did work. Of course, we also have to define what we mean by “work”. Most studies use excess deaths, but we can also look at COVID cases and COVID-specific deaths. But there is another very important, and often forgotten, outcome – flattening the curve (remember that?). Part of the goal was to slow the spread of COVID so that healthcare systems would not become overwhelmed. Is this what we are seeing in the Scandinavian data? Perhaps.

It’s easy to forget, although I know healthcare workers will not, that in 2020 hospitals were overwhelmed with COVID. Patients were literally sharing ventilators. Neurologists were called into cover medical floors. Hospitals were beyond capacity. Other treatments, including cancer treatments, were delayed. Many healthcare workers were traumatized and burned out – let alone affected by COVID itself.

Therefore, there was some value in delaying some cases of COVID, even if in the end the numbers averaged out over time, as appears to be the case on Scandinavia. Of course, there are lots of moving parts here. Omicron and other variants that came later caused their own surges. Policies were fluctuating over time. And the vaccine eventually became available, and how aggressively that was rolled out is a huge factor. The data is complex.

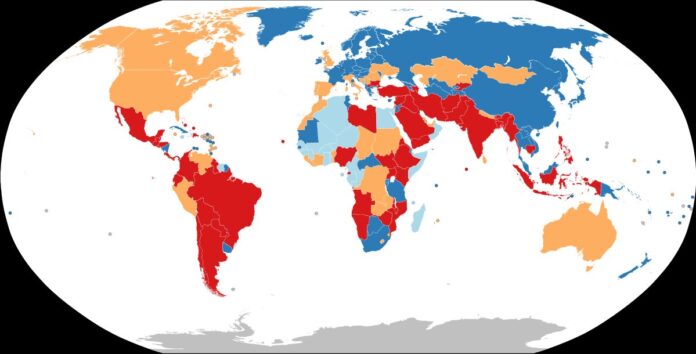

Also, for those countries that did not institute universal mandatory lockdowns, most had measures of their own. Taiwan, which is an island, instituted exhaustive contact tracing, testing, and targeted quarantine. They also had the luxury of limiting travel to the island. It’s important to remember, we are not just comparing lockdowns to doing nothing, but to all the alternatives. Japan had voluntary isolation, but data shows that this was just as effective as mandatory isolation in other countries. But again, Japan has its own culture and voluntary isolation may not work as well everywhere. Sweden limited public gatherings and some gathering places. There is also mask-wearing.

It is possible, therefore, to cobble together something very similar to universal lockdowns with a host of lesser measures that together have a similar result. Which measures are feasible and will work appear to be specific to each country.

What about the risks? It does seem that collectively we underestimated the risks of lockdowns, which is not surprising given that there was no prior experience with anything like COVID in modern times. School shutdowns, which perhaps remain the most controversial, had a negative impact on the learning of a generation. According to recent US data:

“In 2022, only 26% of eighth graders were at or above proficient in math, much worse than before the pandemic (33% in 2019).

Less than a third of fourth graders (32%) were at or above proficient in reading, two percentage points lower than right before the pandemic (34% in 2019).”

These numbers are not catastrophic, but they are significant. Schools were less prepared for online learning that was hoped. They did not have the equipment, the experience, or the curriculum. Families were also similarly unprepared, exacerbated by the existing digital divide.

Social isolation was also not good for mental health, and caused an increase in domestic violence.

But of course, we will never know the counter-factual. What would have happened if we did not close down schools? By how much would that have worsened the pandemic? Many schools had to shutdown anyway due to teacher exposure or illness, for example. Again we are left with data but no clear ultimate answer.

What does all this mean for how we respond to the next pandemic? We were not prepared for COVID – are we prepared for the next pandemic, and what should we do to be prepared? There are some clear strategies that many experts have already pointed out.

First, we need a plan. During COVID the experts admitted we were “building this plane as we are flying it.” This was partly unavoidable, because SARS-CoV-2 was a unique virus and it took time to research and understand it. But there is a lot we can plan for, even for a novel infectious agent.

There are some win-wins we should not neglect, measures with little to no downside. Employers and employees should have a work-from-home plan. If someone is sick, exposed, or just in a high risk area, they should have the capacity and infrastructure to work from home as necessary. This is not possible for all jobs, but for most it is.

Schools likely need a massive investment in their training, preparedness, and infrastructure so that they can shift to online learning, for individuals or entire classes, when necessary while minimizing any downside. This can actually be a net positive, as sick days do not necessarily mean missing class or work. There is data that online learning can be effective in reducing learning loss during shutdowns.

Essentially schools and teachers need a plan for what to do when they cannot have in person class. Just holding a class online does not work. They need a curriculum designed to function online. They may not be learning the same things or the same way, but online learning time can be maximized and can be effective.

For communicable respiratory illnesses, people should have and know how to use masks. They work. Which other methods are likely to be effective, such as hand-washing, should also be communicated to the public when known.

When vaccines are available, everyone should be up-to-date on all recommended vaccines.

There also needs to be a playbook for available options to limit the spread of an infectious illness, including contact tracing, testing, targeted isolation, limiting public interactions, and various degrees of voluntary and mandatory shutdowns. These need to be tailored to the community and to the infectious agent. Perhaps these can even be color-coded levels of response to aid public communication.

Also – this can communicate to the public that the more effectively we institute lower levels of response, the more likely we are to avoid the more draconian measures. Further, if the public is made aware of the possible measures ahead of time, and feel like there is a thoughtful plan in place, they are more likely to accept them when instituted.

We are definitely more prepared now than we were pre-COVID, but not nearly enough. We can’t just forget our COVID experience as a bad dream and move on. That is no longer the world we live in. We need to be perpetually prepared for outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics, with early detection, a host of response options, and high degrees of public buy-in. We are not there.